Chapter 10 - The Short Session

What Newlands intended to do for the West had never been done before. And, as an unremarkable backbencher, Newlands was an unlikely leader to challenge the irrigation status quo.

But for a minor legislative mix-up, one of the most influential laws shaping the West might never have happened. One of Newlands’ friends in the House, Denver Republican John F. Shafroth, informed Newlands that he had just submitted a bill on irrigation. The legislation, Shafroth told Newlands, had been referred mistakenly to Shafroth’s own committee, Public Lands, rather than to the Irrigation of Arid Lands Committee, which should have had jurisdiction. It was a small snafu, but Newlands saw his opening and seized it. Over the course of two years—armed with experts and aided, eventually, by a new and energetic president—Francis Newlands would bring into being the National Reclamation Act, “the boldest piece of legislation ever enacted pertaining to the Trans-Mississippi West.”[1]

What Newlands intended to do for the West had never been done before. And, as an unremarkable backbencher, Newlands was an unlikely leader to challenge the irrigation status quo. But challenge it he did. Fed up with the timidity and backwardness of the western delegation—particularly the states’ rights ideology that hampered effective irrigation measures—Newlands sought to reimagine how Washington approached water projects. Aided by his policy soul mate Newell, one of Newlands’ watermen and an expert legislative draftsman, Newlands would marshal his affinity for regional solutions and technical detail to pioneer a different approach to early 20th century congressional politics.

FRANCIS NEWLANDS AND HIS WATERMEN

Newlands’ career was defined by three high-profile struggles over water management—one in San Francisco (1879-1880), one in Nevada (1889-1890), and one in Washington (1900-1902). In each tussle, Newlands partnered with a skilled technical expert.

Hermann Schussler—Chief engineer, Spring Valley Water Works (1864-1914)Schussler’s engineering and architectural skills were legendary. When Newlands sought to persuade the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to adopt a mutually agreeable new rate schedule for the Spring Valley Water Company, Schussler tutored Newlands in how the company’s complicated cost structure was tied to the size of the city’s population and the size of the city’s public (“free”) water consumption. Newlands distilled the tutoring into language, charts, and graphs that successfully convinced the politicians.

William Hammond Hall—State Engineer of California and consultant to the USGSHall guided Newlands' plan to survey all of Nevada’s rivers for their suitability for dams, reservoirs, and irrigation ditches. Hall had worked in San Francisco with Newlands on the development of the Golden Gate Park and with Sharon on the acquisition of Burlingame. Historian Donald Worster called Hall “one of the country’s leading irrigation experts.”

George H. Maxwell—California lawyer specialized in water rights lawMaxwell was a tireless promoter of irrigation for agriculture development in the arid West. He founded the National Irrigation Congress in the 1890s, of which Newlands was a founding member, and represented Western railroads on irrigation issues. Newlands and Maxwell were early critics of state-run irrigation and early enthusiasts of federal control. Maxwell was a key lobbyist for the Newlands Reclamation Act.

Frederick H. Newell—Chief Hydrographer, USGSTrained in hydraulic engineering at MIT, Newell was one of the leading scientific experts working for the federal government in 1900. Newell worked on the Powell survey of the arid West and was a confidant to Newlands, Gifford Pinchot, and George Maxwell. Having mapped the western rivers that formed multi-state hydrographic basins, Newell joined Newlands in championing a regional approach to irrigation. Along with Newlands, Newell co-authored the Newlands Reclamation Act.

The bill’s winding path into law began in January 1901. Between the election and inauguration of President William McKinley and Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, Congress held a short session of the 56th Congress. Later in life, Newlands noted that he used those few short months—from December 3, 1900 to March 2, 1901—to make a run at passing a comprehensive irrigation bill. After eight years on the outside of congressional politics, Newlands sensed that the political tides had changed in his favor. A vacuum had opened up in the western delegation, and Newlands intended to fill it.

Figure 10.1: Frederick Newell was a pioneer in region-wide thinking, showcased in his mapping of multi-state, hydrographic basins. which he did for the USGS arid-land survey. Newell’s signature regional map, shown here, was titled “The Yellowstone Basin”—not “Wyoming-Montana.” The map is a cartographic lesson in the unsuitability of one state managing a river’s water flow when its flows are multi-state and basin-wide. Note that the Yellowstone basin is split in almost perfect halves by the east-west border line running between Wyoming and Montana.

Drawing on his earlier experience in San Francisco and Nevada, Newlands moved into action flanked with a cadre of technical experts. During the closing months of 1900, Newlands and his friend Newell, the USGS Chief Hydrographer, spent December shuttling back and forth between their separate offices. What emerged from their meetings was a new and comprehensive bill for irrigation in the West. By empowering the Secretary of Interior to determine where and how to build dams and ditches, it broke a longstanding western taboo and administered irrigation on a regional basis that overrode state borders. Newlands introduced their legislation, HR 13846, into the House on January 26, 1901.[2]

As he had tutored the San Francisco Board of Supervisors years earlier, Newlands once more sought to smooth the path of his preferred policy by educating—and entertaining—the policymakers. He mobilized his personal resources—his beautiful Washington house in Cleveland Park, his charming wife and his expert friends—to host “irrigation dinners” for the western delegation. The dinners were great fun, the irrigation education was enjoyable, and the experts were special events in themselves. These experts—like Pinchot, the government’s chief forester, and Maxwell, the longtime irrigation expert who represented the railroads—were charismatic men, on their way up in Washington. Newlands gave five of these dinners in January, three for the House delegation and two for the Senate delegation. The dinners became events in their own right, as the onetime outsider made himself into the consummate insider.

The second dinner was attended by no less than the powerful Appropriations Chairman Joseph G. Cannon and the Speaker of the House himself, David B. Henderson. At it, Newlands spoke glowingly of his new bill and of his commitment to irrigation in the region. His friend Newell gave a lantern slide show, covering ancient irrigation facilities in exotic India, contemporary small-scale irrigation facilities in the West, and slides from the famous Powell survey of river basins in the arid West. The assembled members of Congress were dazzled.

The dinners paid off, but it was the committee confusion that provided Newell his first major opening. Frank Mondell—the Wyoming Republican that Mead had alleged didn’t “know enough about either” forestry or irrigation—served on the House Irrigation Committee, which he kept dormant unless Senator Warren made a legislative move in the upper house. The accidental referral of Shafroth’s bill to the Public Lands Committee neatly avoided Mondell’s legislative graveyard. Newlands and Shafroth persuaded the Public Lands Committee to accept Shafroth’s bill and commence hearings. Next, in an act of legislative jiu-jitsu, Shafroth substituted Newlands’ bill for his own.

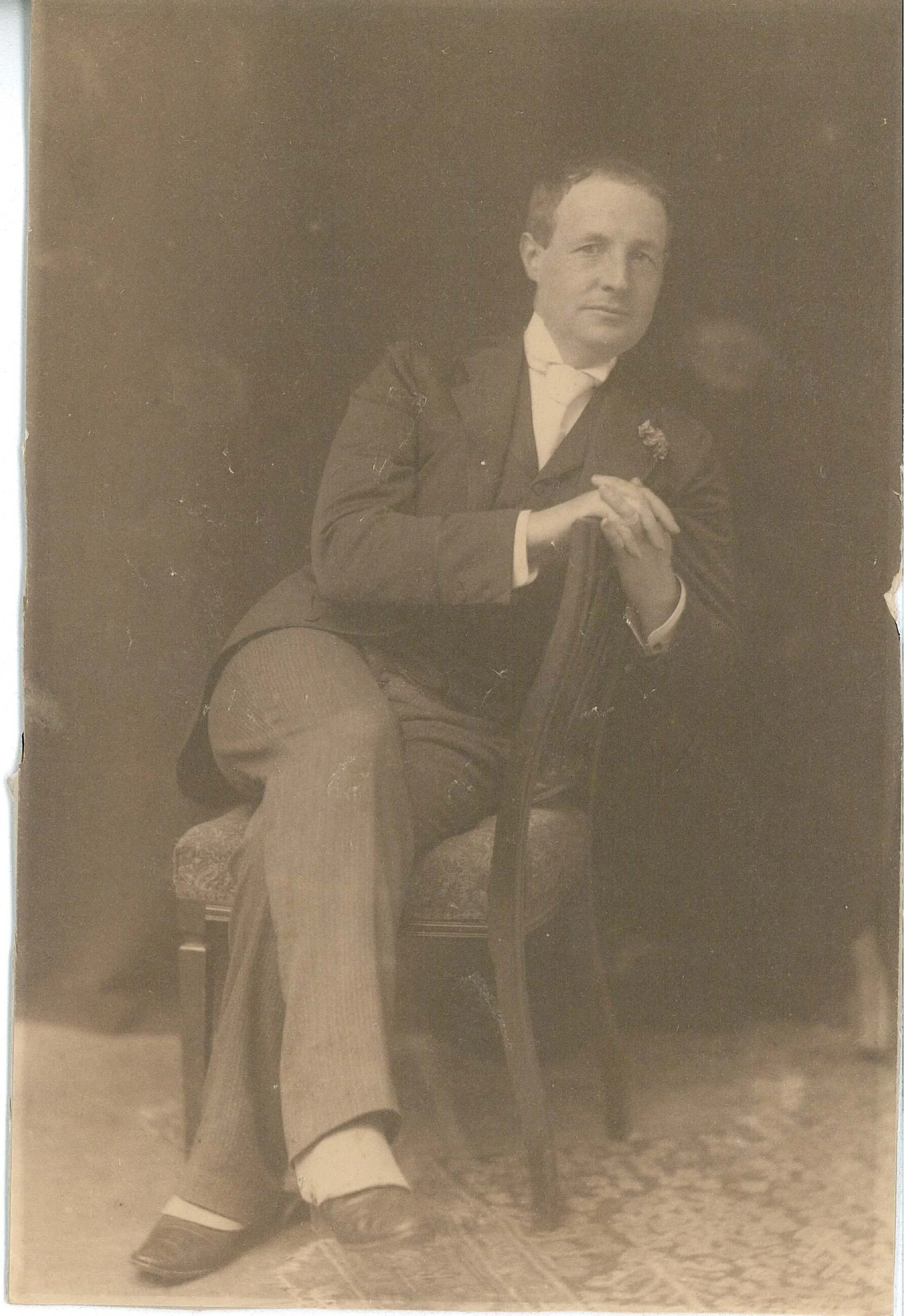

Figure 10.2: Newlands in Washington 1900, at peak of House career while drafting his reclamation bill. Newlands “weekended” at his country estate in nearby Chevy Chase (MD) which Newlands developed as the country’s first “suburban new town.” He fancied himself an Edwardian gentleman, was an avid horseman, and dressed accordingly. Note the spats.

The hearings were set for January 11 and Newlands was given permission to arrange the witness list. He produced a list notable for its heavyweights, a sign that his time had come. Testifying in front of the committee were Newlands himself, as well as Maxwell, the executive chairman of the National Irrigation Congress and a frequent guest at Newlands’ dinner parties. Representing the USGS were Newell, the USGS Chief Hydrographer; N. H. Darton, the Chief Geologist; and Charles D. Walcott, the USGS Director. From the Interior Department came Pinchot, the Department’s Chief Forester, and E.A. Hitchcock, the Secretary of Interior himself. Mondell, a member of the committee in addition to his membership of the Irrigation Committee, asked to provide rebuttal witnesses. Arrayed against Newlands’ heavyweights were Mondell himself and Elwood Mead, the Agriculture Department’s irrigation expert. It was the best that the states’ rights side could muster, and they paid dearly for it.

What happened next foretold what would happen, again and again, when irrigation came up for consideration in the House. Whenever the nationalists and statists were pitted against each other—in hearings, in testimony, or before committee meetings—the nationalists were inevitably better armed and disciplined. By stark contrast, the hapless statists in the western delegation had no experts and no discipline.

“The final conclusion has been reached that the Committee on Public Lands will assume jurisdiction of this subject,” Newlands observed at the January 11 hearing.[3] Newlands noted that Public Lands “is a live committee and an active committee, and fully familiar with the land laws and the settlement of the western region and is probably better qualified than any other to take up this question.” The operative words were “live” and “active,” in stark contrast to Mondell’s moribund Irrigation committee. By producing a top-flight group of experts who demonstrated their easy expertise and prowled for bureaucratic influence over irrigation, Newlands guaranteed a “live”—and, indeed, lively—hearing on his bill.

The four-day hearings went well for the debut of HR 13846. The looming question was, “Would it work?” One by one, the expert witnesses were grilled on—and attested to—the feasibility of an irrigation scheme that encompassed the entire arid West. Collectively, Newlands’ witnesses acquitted themselves handsomely.

Newlands himself put on a sparkling performance. He knew the bill thoroughly, and he knew how and where irrigation worked and didn’t work. After Spring Valley and years trudging around the Truckee, Newlands’ detailed knowledge of water issues extended to how much irrigated water a crop required on a per acre/per year basis.

Newell and Maxwell also weighed in with their substantial expertise, the former a known commodity from his lantern slide shows at the Newlands’ dinners and the latter known to speak for the railroads. The Interior Department officials, most of them from the Geological Survey, jumped on the Newlands bandwagon. As they saw it, the bill would vastly increase the Interior Department’s power, and within the department, the Geological Survey’s power.

Perhaps the most interesting testimony came from Pinchot. He saw the irrigation movement as inevitable, and was intent on using the opportunity to promote his cause—forestry—as a key partner. While other witnesses talked about irrigation’s value to agriculture, Pinchot discussed how reservoirs needed forests in order to function properly. As presented by Pinchot, forestation was more interesting than agriculture. Pinchot had the rare ability to speak as if whatever he uttered was new. Gifford Pinchot made forestry new to irrigation.

The hearings were smooth sailing until the third day, when Mondell testified against the bill. In fairness to Mondell, he never should have been in the ring with the likes of Newlands, Newell, and Pinchot. Mondell was cast perfectly to play the role of a non-commissioned officer in the western delegation. But he was not officer material. He came out of the Wyoming Territory, rising from rancher to mayor of Newcastle (population 659 in 1890). Mondell then graduated to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he became Senator Warren’s man in the House. Inadvertently, the inept and cantankerous Mondell became Newlands’ “secret weapon” in this legislative battle.

Mondell’s task was to put a positive spin on the states’ weakened irrigation position. He botched the job. Mondell struggled to explain what he called “the demarcation line” between the federal role and the states’ role in irrigation, venturing that the federal government did “conservation and construction” while the states did “application.” Mondell had the party line right. But lacking the background to extrapolate concept into actual practice, he stumbled. Embarrassingly, Mondell asked if he could return the next day with an expert. The next day he showed up for an anti-climactic repeat performance, with Elwood Mead by his side. For unexplained reasons, Mead left abruptly. It was a typically bungling performance from Newlands’ opponents.

Nevertheless, Mondell persisted. Attempting once again to seize the initiative from Newlands, Mondell cajoled his Irrigation Committee into holdings hearings on his own bill, HR 14165, which again attempted to establish that “line of demarcation” and leave to the states the “application” of stored water. Hearings were held January 28, February 7, and February 9. Yet in trying to brake Newlands’ momentum, Mondell made the tactical error of staging his show while Newlands was simultaneously holding carefully-orchestrated hearings and dinners on his own proposal.

Instead of being upstaged, Newlands stole the show. He gained permission to bring his expert witnesses to the Mondell hearings to promote the Newlands bill. Once again, the Newlands team—Newlands, Newell, Pinchot, Maxwell, and Darton—championed their nationalist approach. Mondell testified next—and inserted his foot into his mouth. He was not a lawyer, he said, but he thought it “was unconstitutional to actually irrigate land and peddle water.” The committee construed Mondell’s remarks as a western challenge to the House’s favorite legislative activity—“rivers and harbors appropriations” for dams and dredging.

Challenging Mondell on that point, Congressman William King, a Utah Democrat, asked Mondell, “Is there any difference between having a dam to store flood waters and building a dam… for reclamation of extensive tracts of land?” Once again, Mondell fumbled. “I do not think there is a great difference,” he answered. The Mondell rebuttal to Newlands’ position was so weak as to be modestly harmful.[4]

With the hearings in the Irrigation Committee behind him, Newlands returned his focus to the Public Lands Committee. He visited with the six western Republican members on the Committee to ask for their support. Mondell he wisely excluded.

To Newlands’ dismay, the six were too timid to step forward. Appropriations Chairman Joe Cannon of Illinois—a dominant force in the House and future Speaker—frequently deprecated and bulldozed the western states, which, with the exception of California, had only one or two members. Cannon made a point of keeping the western delegation off of the rivers and harbors bill. Fearing retribution from their leadership, none of the Committee Republicans were willing to cross the “Tyrant from Illinois.”

Redoubling his efforts, on February 18 Newlands wrote a four-page letter to the six Republicans, urging them not to fear the anti-western sentiment of the House leadership. If the Public Lands Committee referred the Newlands bill to the Rules Committee, he reasoned, the worst that committee could do was reject it.[5]

Newlands tipped his hand to the House Public Lands Committee as to why he needed a referral. He explained in the letter that he had been hard at work on fellow Westerners in the Senate—and they had agreed to support his bill. The Westerners on the Senate Public Lands Committee were especially enthusiastic. Newlands had held two dinners for western senators, just like the ones he had held for the House members. At the second dinner, Senator Richard F. Pettigrew, a South Dakota Republican, had moved that the delegation support Newlands, which it did unanimously. He then moved that Senator Henry C. Hansbrough, a North Dakota Republican and Chairman of the Senate Public Lands Committee, introduce the Newlands bill as his own and move it through committee. Hansbrough agreed.

With the Senate prepared to move, Newlands asked the House Republicans, why was the House Public Lands Committee so fearful of “rapidity of action?” Yet Newlands’ attempt to embarrass the committee’s Westerners made no impression on them. As Newlands later told President Roosevelt, their fear of Cannon was too ingrained.[6]

Newland’s letter was dated February 18, only 10 days before the adjournment of the 56th Congress. With time running out, Newlands appealed to the Public Lands Committee to put his bill on the floor, hoping that a Senate companion would be coming over to the House for a conference committee. Hansbrough nearly got it done. His Senate committee reported the bill to the floor and Hansbrough attached it to the catch-all Civil Sundry Bill. But the parliamentarian objected that Hansbrough’s bill was a general bill, not an amendment. On March 1, the parliamentarian’s ruling was sustained, 34-20.

Congress adjourned. In three short months, Newlands had accomplished three key breakthroughs. He’d drafted his bill. He’d built a cadre of experts. He’d assembled congressional support. But Newlands’ magisterial performance wasn’t enough. At the end of the short session, the nationalists had come up short. If he had any hope of achieving his long-held irrigation ambitions, in the coming months, Newlands would have to try again.

[1] Donald J. Pisani, To Reclaim the Divided West: Water, Law & Public Policy, 1848-1902 (Albuquerque, 1992) p. 322.

[2] Newlands, Sheridan speech commemorating the Newlands Act of 1902, June 30, 1905, Newlands mss. Hereafter Newlands, Sheridan speech. The Newlands Act is reprinted and summarized on pp. 79-82. Newlands and Newell were the veritable two peas in a pod when it came to water management. They thought alike about rivers. Newell was interested in the “the nature of the river,” while Newlands cared about “the system of the river.” That kind of thinking led into “river basin” thinking, which in turn led into regional thinking. Newell knew that “river basin” thinking was contrarian, and he delighted in it. He lunched daily at the “Great Basin Lunch Mess,” a prominent table in the center of the dining room of Washington’s Cosmos Club, a haven for scientists and experts. Newell founded “the Mess,” and Gifford Pinchot was the first to sign up. There is a delightful gem of a biography of Newell by Donald J. Pisani, the authority on public lands. See Pisani, “A Tale of Two Commissioners, Frederick H. Newell & Floyd Dominy,” History of the Bureau of Reclamation (Las Vegas, June 18, 2002) available online at www.waterhistory.org.

[3] House Committee on Public Lands, 56th Congress, 2nd session, Hearings on HR13846 Reclamation of Arid Lands, Testimony of Rep. Francis G. Newlands, January 11, 1901, pp. 7-34.

[4] House Committee on Irrigation of Arid Lands, 56th Congress, 2nd session, Hearings on HR 14165, January 28, 1901, Testimony of Rep. Frank Mondell, pp. 57-68.

[5] Newlands to House Public Lands Committee, February 18, 1901. Newlands Mss.

[6] Newlands, Sheridan speech.