Chapter 8 - Trouble on the Truckee

Newlands set out to bring Mead’s same scientific approach to Nevada. It was “an elaborate effort” for irrigation development in the state.[1] First, he hired a highly-regarded accounting firm from Manchester, England to identify and value Sharon’s estate—especially its irrigation assets. For years, Sharon had owned the Virginia and Gold Hill Water Company in Virginia City, which drew water from deep within the Sierra Nevada mountain range. He had also bought vast tracts of land in Burlingame, California and Phoenix, Arizona, both of which would require irrigation for development. The accountants took a hard look and concluded that the Sharon estate was Nevada’s second-biggest property owner, right behind the Central Pacific Railroad.[2]

Next, Newlands assembled a team of irrigation experts—engineers, water law specialists, and geophysicists—whose comings and goings were reported in the Nevada press. Newlands’ team was headed by William Hammond Hall. Considered by one historian to be “one of the country’s leading irrigation experts,”[3] Hall was a big “catch” for a study of Nevada. Hall was known throughout the West as California’s preeminent irrigation engineer. He had been involved in John Wesley Powell’s renowned irrigation surveys for the U.S. Geological Survey, and shared with Newlands drafts of the USGS surveys for the Truckee and Humboldt river basins.[4]

Figure 8.1: The Truckee River at spring runoff

Figure 8.2: The Truckee River in Nevada, fed by the run-off from Lake Tahoe, flows between Reno and Truckee Bluffs. Newlands solitary house, built in 1890, perches on the bluffs at Rattlesnake Point. The size of the house, and its separation from Reno, attests to Newlands status as Nevada’s “peacock in the chicken yard.” The photos capture the difference between mountain West rivers at spring flood run-off (left) and placid summertime (right).

Newlands put his experts to work surveying all the rivers in the state suitable for dams and reservoirs. For his irrigation ambitions to come to fruition, it was imperative that Newlands know the right places to capture the spring floods. In the summer of 1890, after a year of intensive effort, Newlands published the results of his team’s surveys in a sleek pamphlet entitled General Plan for the Irrigation and Reclamation of the Arid Lands of Nevada.

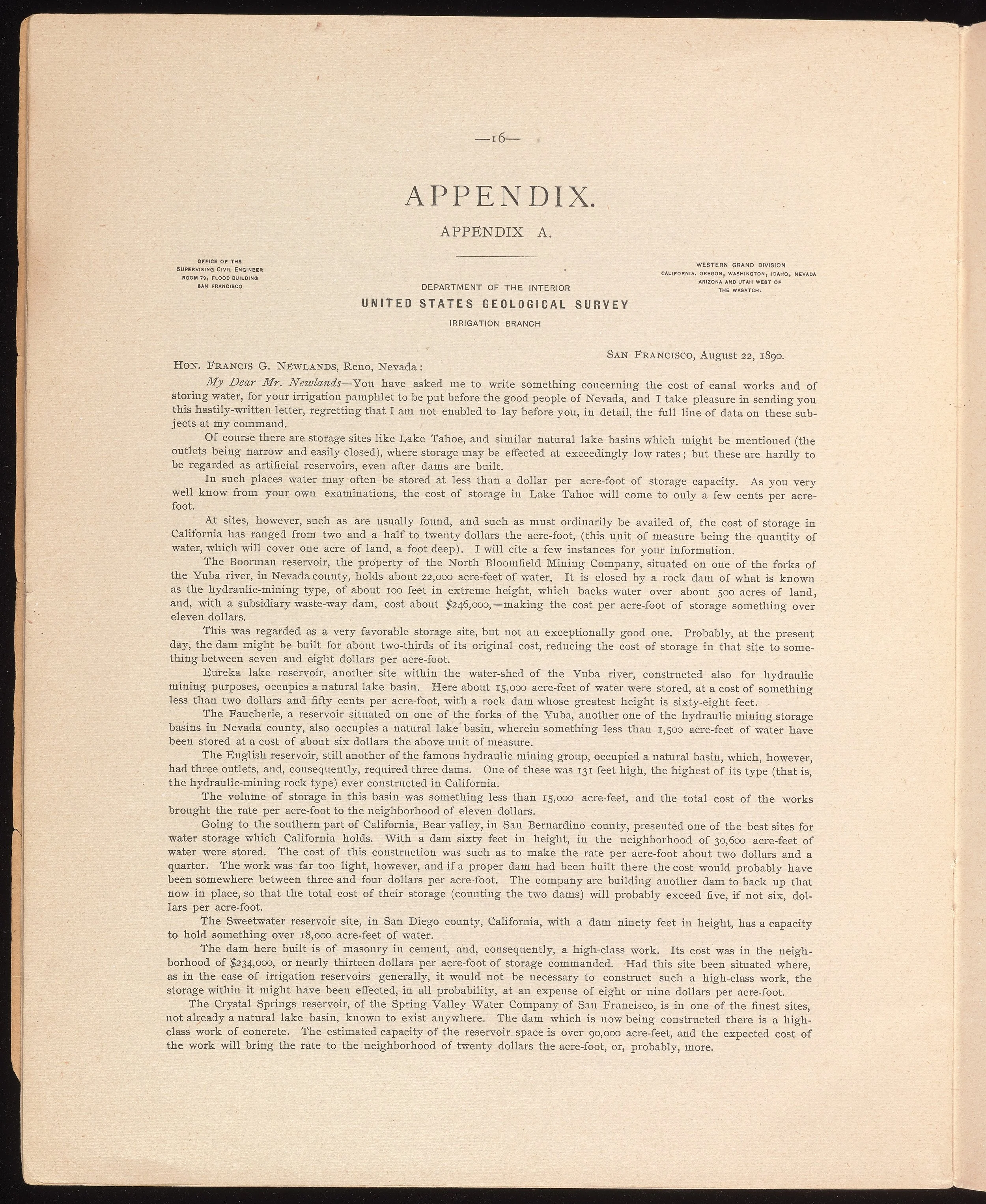

Figure 8.3: Newlands’ irrigation plan dazzled the Nevada press, citing the maps and diagrams. The reliably skeptical Carson City Daily Appeal praised it in contrast to “the useless and wholly impractical work of Major Powell.”

The Nevada plan was an important milestone in Newlands’ career. It also marked a high point in the irrigation boom in the West. The pamphlet ran 26 pages, punctuated with colored maps and tables. Infused with idealism, expertise, and a call to overhaul both the state economy and the state government, it was distributed free to every registered voter.[5]

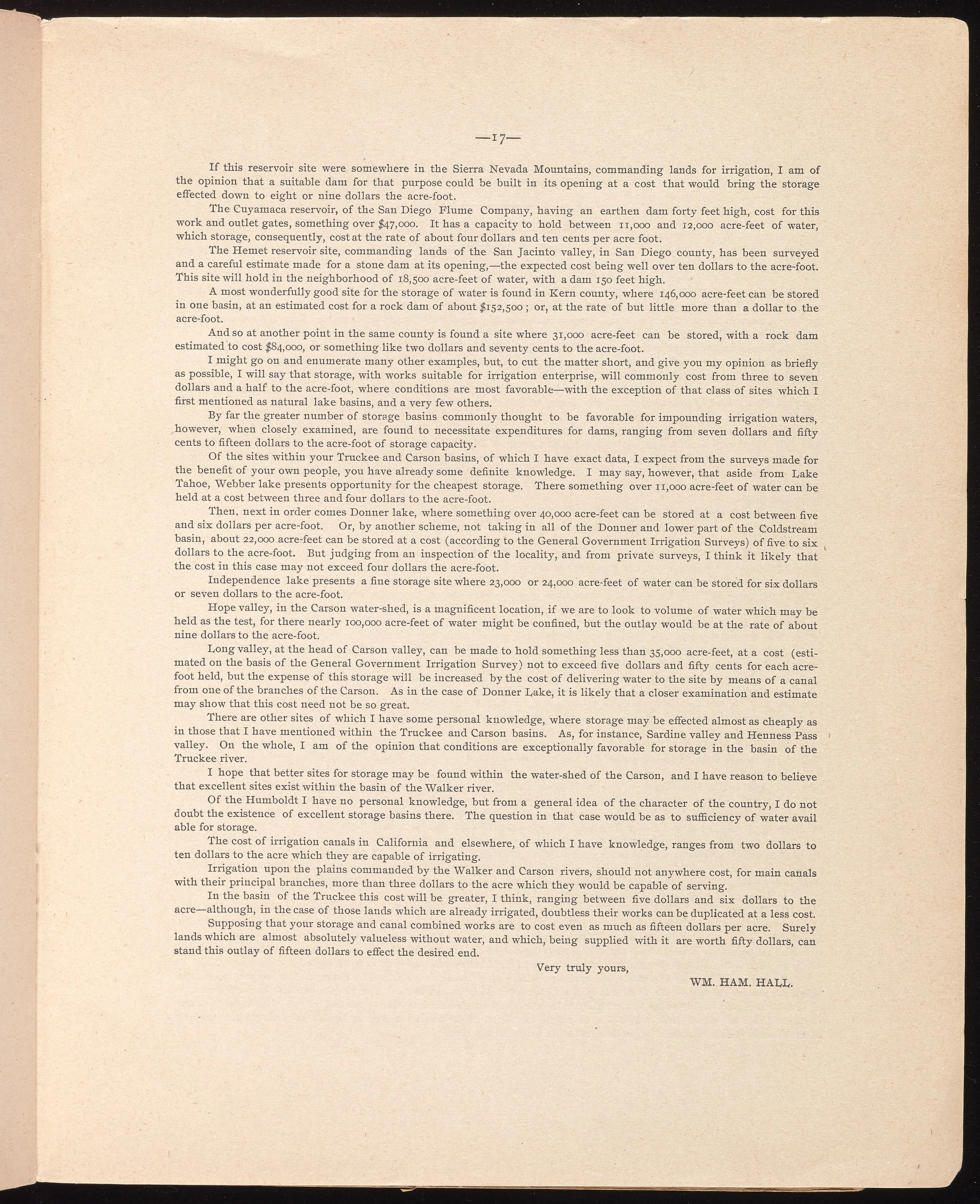

Apart from the pamphlet’s overall thoroughness, two pieces of content are noteworthy, both shown here. One is the official letter from Hall to Newlands, telling developers where to buy irrigable land. The letter is written on Hall’s stationary (highlighted in yellow), identifying Hall as the Chief Supervising Engineer for the Western Division of the U.S. Geological Survey. As was not unusual in the Gilded Age, Newlands and Hall were acting out roles that blurred the distinction between private power and public authority. Hall’s letter reviews each water storage site on Nevada’s lakes and rivers, ranks each according to storage feasibility, and calculates the cost to store water at each site. Highlighted in yellow are the estimates for the Truckee project, which Newlands favored as most feasible for development.

Click the image of the letter above to view excerpts

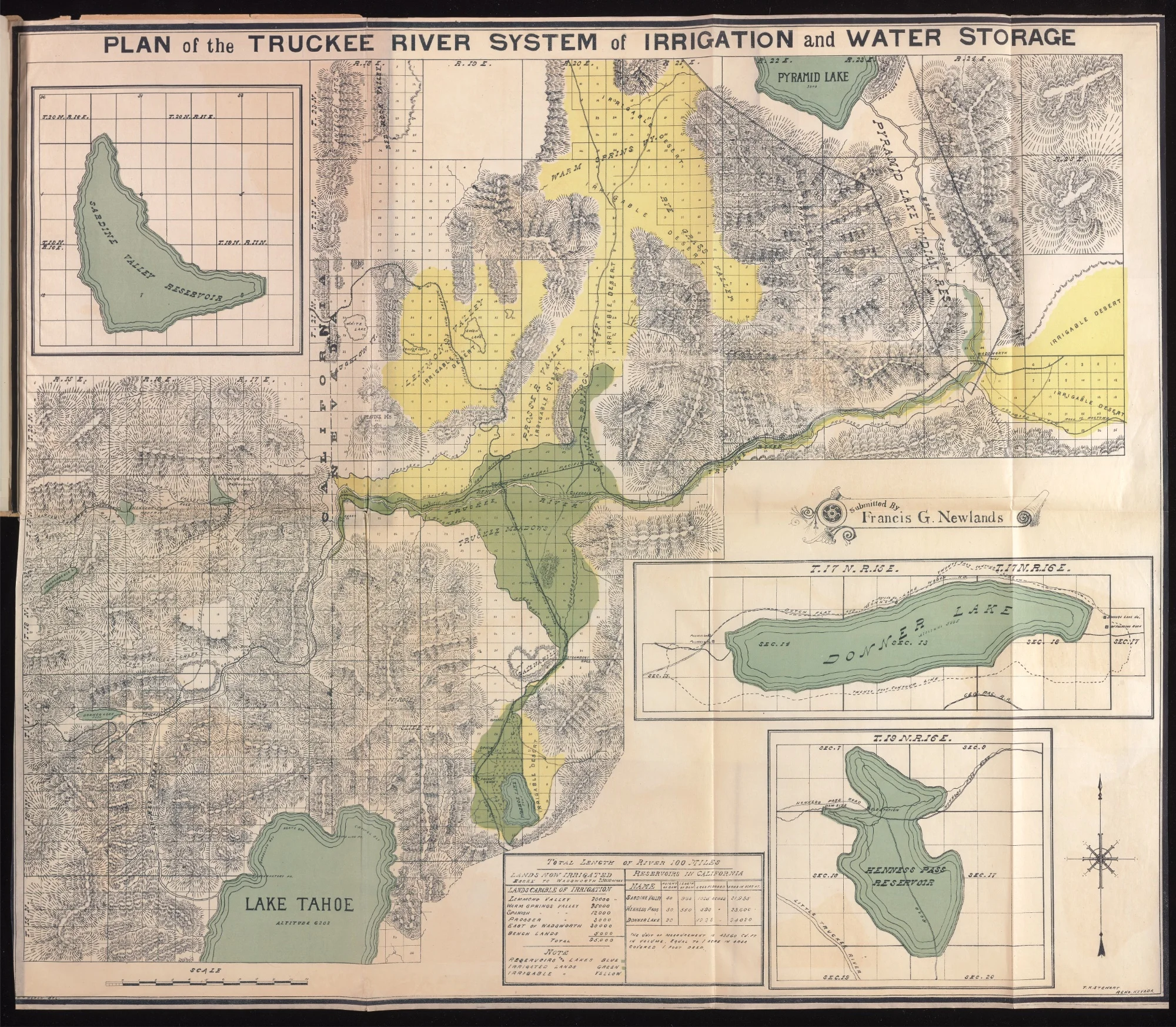

Also notable is a map of the Truckee project (shown below), if it were developed according to Newlands’ plan. The Truckee runs 100 miles from Lake Tahoe to Pyramid Lake. Blue coloring indicates lakes and rivers, green indicates land under irrigation, and yellow indicates irrigable land.

The plan put Newlands at the head of the boomer parade. And he moved quickly to capitalize on it. Not only had Newlands surveyed every river with an eye to irrigation, he’d also begun purchasing the relevant properties, starting with the Truckee River.

The Truckee was the sole outlet for Lake Tahoe, draining eastward through the Sierra Nevada range, through Reno, terminating about 40 miles outside the city into Pyramid Lake. Newlands’ plan for the Truckee system was audacious—and comprehensive. He bought an option for a dam site at Lake Tahoe, another on the Little Truckee, and, for good measure, three other sites on the neighboring Carson River. He bought an option for a reservoir site at Little Truckee Canyon. Recognizing that the irrigation developer would need to sell land to finance construction, he negotiated to buy land adjacent to the sites as well. In short order, Newlands had bought options at all the suitable dam sites on the Truckee River.

Newlands offered to sell his options to the state of Nevada at cost plus six percent—either to the state itself, or to a reclamation commission or an irrigation district. His one condition was that the state authorize an engineer to supervise construction and create a state reclamation commission to manage the system.[6]

Even as he bought up dam sites, Newlands was cajoling the Nevada legislature to adopt proposals he had broached in his plan. These proposals moved smoothly. The irrigation boom was popular in the West and Newlands was identified with it. He was new to Nevada politics and he was wealthy. He was also easygoing, as was his top lobbyist, William E. Sharon. “Willy” Sharon was the former Senator’s nephew and, as “the young Sharon,” had managed the family’s political affairs in the 1870s. Crucially for the chances of Newlands’ legislation, Willy also happened to be the majority leader of the Nevada Senate.

Throughout 1889, irrigation reforms coursed through the legislature like water through a spillway. The legislature created a state irrigation engineer, to supervise irrigation work in the state. They enabled counties to float irrigation bonds issued by local irrigation districts. They created a board of State Reclamation Commissioners, and empowered the board to construct and manage irrigation facilities. They approved $100,000 to start dam construction, and then authorized the Commission to use the untapped $700,000 state school fund for irrigation work. One might have looked upon Nevada in that heady moment and proclaimed it, too, to be “Law Giver of the Arid Region.”

Yet the zeal for irrigation reform dried up as quickly as it had begun. The first test was the relatively small $100,000 appropriation to buy out Newlands’ dam site options. While modest, the appropriation ran up against pork barrels. There were the “best” dam sites for irrigation and the “best” dam sites for the political districts of the senators—and rarely did the twain meet. The Senate finance committee deadlocked.

The failed appropriation started a cascade of reversals. The reclamation commissioners stopped meeting, because the state treasurer challenged their authority to tap the school fund. The state attorney general argued that counties could not issue bonds, which would compete with the state’s issuance of bonds. The state engineer’s job, the final piece of Newlands’ irrigation architecture, was never filled. In 1890, the legislature struck down what it had enacted the previous year. After all of Newlands’s work—after his extensive surveys and well-packaged irrigation pamphlets, his favorable press coverage and the encouraging initial actions of the legislature—Nevada was nowhere.[7] So much for the irrigation boom in the Silver State.[8]

Newlands always believed that the state failed him in carrying out his plan, particularly the Truckee project. Smythe, who endorsed the Newlands plan, wrote that “it came to nothing because of public indifference and subtle opposition.”[9] William Rowley, Newlands’ biographer and the dean of Nevada historians, pointed the finger for that “subtle opposition” at Nevada’s livestock operations. In his article Opposition to Arid Land Irrigation in Nevada, 1890-1900, Rowley noted that the state’s livestock industry was fundamentally opposed to irrigation for agriculture. The livestock interests were ever-present in the state legislature. Newlands and the irrigation interests came and went.[10] When push came to shove, the cattlemen carried the day.

The entire irrigation escapade in Nevada taught Newlands a valuable lesson. He became convinced that state governments by their very nature were unable to administer basin-wide irrigation programs. They were too politicized to manage something so complex—and too inept, to boot. The politics of the appropriations process, so central to legislative politics, bothered Newlands particularly. His plan for Nevada had foundered specifically on the legislature’s inability to appropriate a measly and already authorized $100,000. To keep funds flowing but escape the appropriations trap, Newlands would have to find a novel way to finance irrigation projects.

“In she plunged boldly/No matter how coldly/The rough river ran…” At one of those long-ago Bohemian Club evenings, Newlands—a young romanticist on his way up—had reflected on Thomas Hood’s poem, and his suffering subject’s losing battle with the Thames. “Over the brink of it/Picture it—think of it/Dissolute Man!” Through his work, wealth, and willpower, Newlands had brought arid Nevada to the brink of harnessing its several rivers. But to finally capture the waters of the West, Newlands would have to go back East—to Washington.

[1] Smythe, p. 205

[2] J.R. Bridgford & Sons, chartered accountants, Manchester, England, “Balance Sheet, Sharon Estate, January 1, 1890" & “Analysis of Sharon Estate, 1889-1890,” Sharon Estate, 1889-1890.” Newlands Mss. See also, Lilley, “Early Career,” p. 194.

[3] Donald Worster, Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West (Oxford: NY, 1985), pp. 110-118, quote p. 117. See Lilley, Early Career, p. 199, footnote 19. See also Reno Gazette, October 8, 21-22. Also William Hammond Hall to Charles F. Crocker, January 5, 1891, Newlands Mss.

[4] See William H. Hall to Newlands, January 9, 1890, Newlands Mss. Richnak, River Flows, pp. 85-89 discusses the Hall-Newlands collaboration.

[5] The document is available for examination and photocopy in the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale.

[6] Newlands’ General Plan is discussed in detail in Lilley, Early Career, in the chapter on “Politics in Nevada, 1888-1892,” ch.6, pp. 190-240. Also, see Lilley & Gould, Western Irrigation Movement,1878-1902 (Univ. of Wyoming, V. XXXII (1966). pp. 59-60 for more details. The on-the-scene mapping and printing is discussed in Richnak, A River Flows, pp. 85-86.

[7] See Reno Gazette, Oct 17, 1889, “What F.G. Newlands is doing to develop our State.” The ups and the downs for the Newlands plan are summarized in Newlands' talk to the Nevada Board of Trade, January 6, 1891, with attachment Correspondence concerning Water Storage and Reclamation of Arid Lands in Nevada (Reno, 1891), Newlands mss. Rowley, Career of Francis G. Newlands, p. 65, and ch. 6 “More than Noble Words.”

[8] More information on Newlands’ legislative reforms is in Lilley & Gould, Western Irrigation Movement, 1878-1902, pp. 59-62

[9] Smythe, p. 205

[10] William D. Rowley, Opposition to Arid Land Irrigation in Nevada, 1890-1900. Annual Report, Assoc. Pacific Coast Geographers, v. 43 (1981) pp. 113-123. After the Newlands Reclamation Act became law in 1902, Newlands still kept a close eye on the Nevada legislature and irrigation matters. He told Frederick Newell, his longtime ally and the first Director of the Reclamation Bureau, that he had always wanted a bill “which will give your department as free a hand as possible in this state.” FGN to Newell, February 6, 1903, Newlands mss. Quoted in Donald J. Pisani, Water, Land and Law in the West: The Limits of Public Policy, 1850-1920 (Kansas, 1966), p. 41.