Prologue

The Gilded Age West was good to Frank Newlands. It made him rich and influential, even famous. At the tender age of 21, Newlands arrived in San Francisco, penniless and jobless. Glamorous and dangerous, the city was wide open for a young striver. Just four short years after his arrival, Newlands was general counsel of the Bank of California, general counsel of the Spring Valley Water Works, and—crucially for his future—the son-in-law of William Sharon, the richest man in the city.

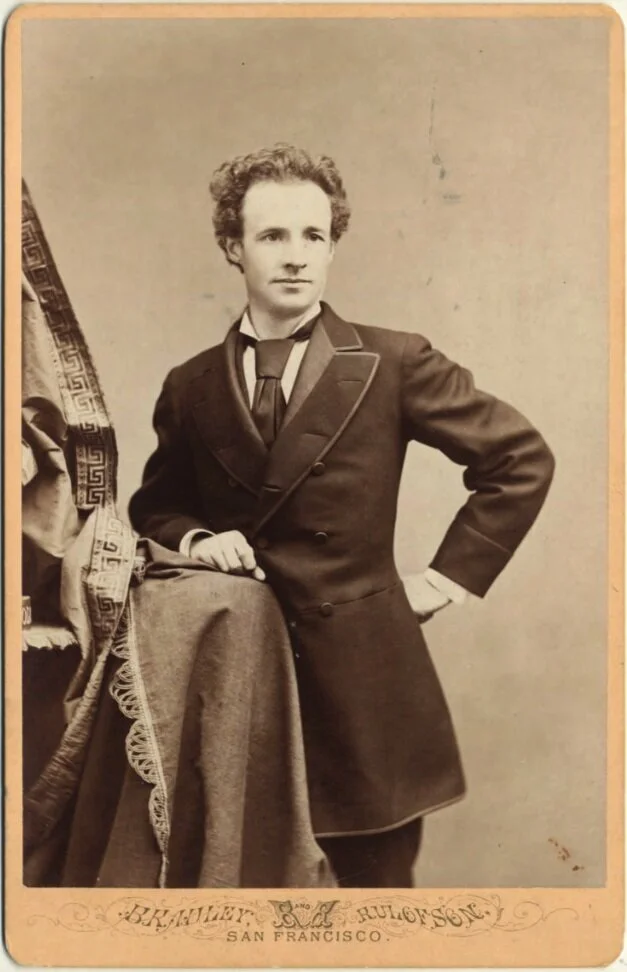

Francis G. Newlands shot by Carleton Watkins

Working closely with his father-in-law, especially on water projects, Newlands quickly learned that success required thinking on a large scale and relying on technical experts. He managed businesses that were regional in scope and required deep engineering expertise. Newlands’ business career was a long tutelage in managing water—how to acquire it, how to conserve it, and how to make money from it. It was also a tutorial in overcoming setbacks both personal and professional, as Newlands found himself exiled to dreary Nevada, only to use the state as a springboard to national politics.

By the end of the century, Newlands was in Congress and at the vanguard of the Progressive Era. His long love affair with western water positioned him perfectly to almost single-handedly bring into being the National Reclamation Act. In turn, that landmark law marked the beginning of a long national effort to conserve, dam, and harness the big interstate rivers of the American West.

This study details how that happened. It tells the improbable story of an obscure Nevada Congressman who drafted the bill and shepherded it into law. It’s a story about an Eastern-educated western businessman who tumbled into alkali-ridden western politics, all the while promising his family that he had no intentions of becoming “a Nevada politician.”

over the course of two crucial years, Frank Newlands educated, cajoled, and maneuvered to passage one of the most significant laws ever to shape the American West. He dreamed of an approach to irrigation that mirrored “the system of the river.”

It’s a story of political perseverance, strange bedfellows, and impeccable timing. By standard political rules, Newlands had no business writing and passing what became the National Reclamation Act. He was an outsider to the western Congressional delegation. He had no interest in these states’ territorial pasts and disdained western political beliefs in states’ rights and the sanctity of state borders. He hardly even lived in Washington, D.C. Yet over the course of two crucial years, Frank Newlands educated, cajoled, and maneuvered to passage one of the most significant laws ever to shape the American West. He dreamed of an approach to irrigation that mirrored “the system of the river.” And he achieved it.

Like the roaring rivers he spent a lifetime seeking to tame, Newlands’ career was a winding one. It boiled with frenetic forward motion, transcending arbitrary boundaries of place and profession. There were moments when his power slowed to a trickle. At other points, it burst forth unrestrained. By the time his career had run its course, the West would be changed forever.