Chapter 3 - Son-In-Law

As Frank Newlands and Clara Sharon pledged their undying love to one another, all eyes were on someone else—William Sharon. As local luminaries gathered at Sharon’s large and lavish home on November 19, 1874, the bride and groom were but bit players in their own nuptials. William Sharon was the star, and he put on quite a show.

Sharon’s wedding staff gave the press a guided tour of his ritzy residence, included photographing all the furnishings—even the sheets in the bridal bedroom—and the price tags conspicuously adorning them. The wedding itself was a brief event, limited to immediate family, followed by a massive reception with 800 members of San Francisco’s rich and famous. The entire invite list was published in the Chronicle, which ran a special edition of the paper. Three whole pages—including the front page—were devoted to the wedding, which the paper treated as if it were the wedding of the century.

Sharon made sure that copies quickly found their way across the state line to, of all places, Nevada. One of Nevada’s first two U.S. Senators, William Stewart, had recently decided to retire and return to practicing law and overseeing his “disastrous” mining operations.[1] The Nevada legislature had until January 1875 to fill the vacant seat. Befitting the diversity of Gilded Age politics, William Sharon, the mine owner, had designs on replacing William Stewart, the mining lawyer.

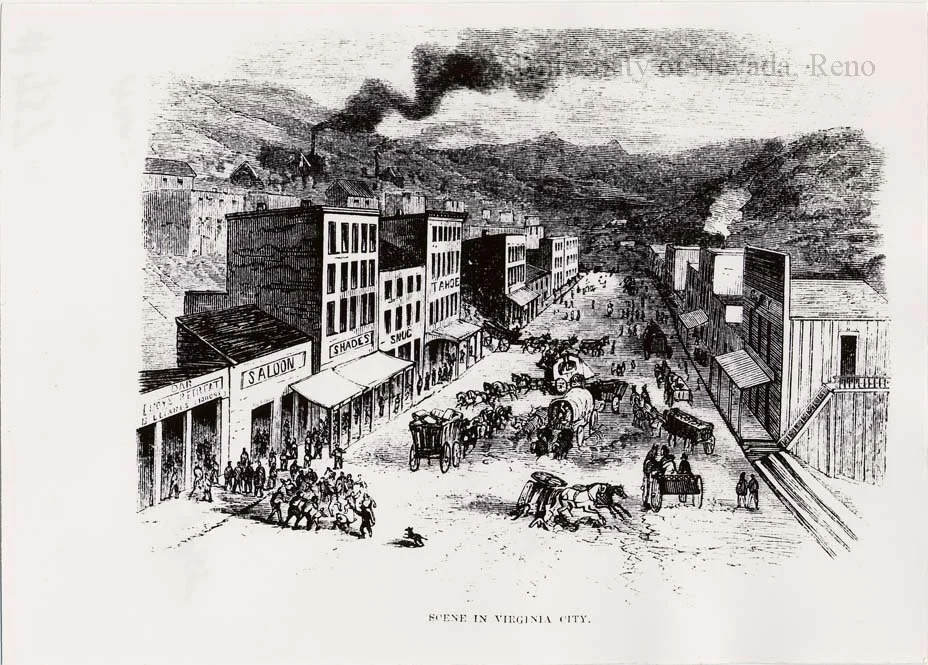

Figure 3.1: Virginia City, 1864 - Lithograph shows a frenzied frontier mining town in a year of silver bonanzas. C Street, the main drag, runs east to west, ending abruptly where snowshoe paths start uphill to the silver mines, the stamping mills and the Sierra Nevada. The Bank of California is on the southerly corner of the second block. The Territorial Enterprise is on the third block, and the Wells Fargo stagecoach stop is on the 4th block (TAHOE is emblazoned on the building.)

Sparsely populated, only a decade removed from statehood, Nevada remained a plaything of wealthy and powerful interests in California—the “rotten borough” of San Francisco. Accordingly, Sharon opened his campaign not on the hustings in Nevada but in a ballroom in San Francisco. Shrewdly, Sharon sought to send a message to the Nevada legislature that he was even richer and more influential than anyone had imagined. The two wedding toasts were made by California heavyweights Leland Stanford and George Hearst, both soon-to-be senators from the Golden State. Each singled out Sharon as a prospective Nevada senator. So did Ralston, the master of ceremonies. In one fell swoop, Sharon simultaneously married off his oldest daughter and kicked off his campaign.

In one fell swoop, Sharon simultaneously married off his oldest daughter and kicked off his campaign.

With such powerful backing, Sharon handily won the seat. But Sharon’s tenure in the Senate would ultimately become a fiasco, both for Sharon and for Nevada. As he presided over Newlands’ wedding, little did Sharon know that his single undistinguished Senate term would eventually invite the ridicule of the press and the embarrassment of his children.

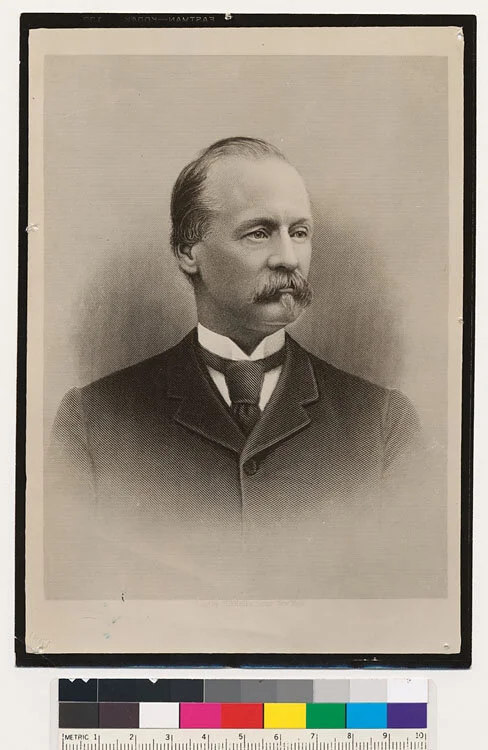

Figure 3.2: William Sharon in his forties in Virginia City. Known as the “King of the Comstock,” the dour titan is a slight man with thinning hair. Only rarely was Sharon photographed without his trademark black banker’s hat.

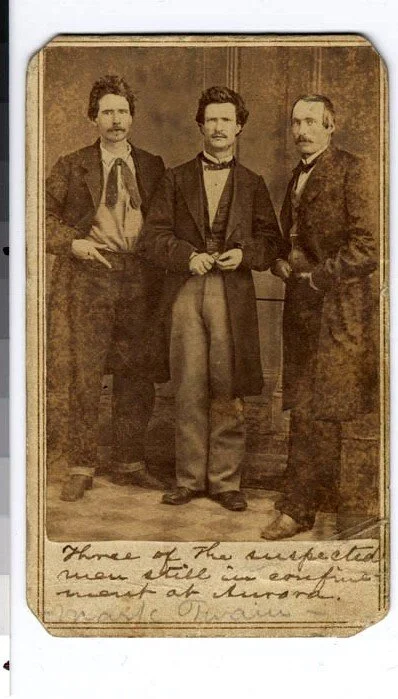

Figure 3.3: Movers and Shakers, Virginia City 1864. Mark Twain at 29 flanked by William H Clagett and A.J. Simmons. The trio pooled their funds to speculate in silver mines on which they had been tipped. Twain’s columns in the Territorial Enterprise (rerun in the San Francisco papers) made him a local celebrity. Simmons was speaker in the territorial assembly and “Billy” Clagett, also a member of the assembly, was active in Nevada silver mining.

Frank Newlands could have seen it coming. In 1872, Sharon’s devious dealings had become the talk of the city’s mining exchange. What happened—and how it happened—said a lot about Sharon’s character, and the Gilded Age West’s. Events came to a head on May 15, 1872, as Newlands was courting Clara. The incident involved the Crown Point silver mine in Nevada’s Comstock region. Sharon owned one-third of the shares, but mine employees were secretly contesting his control. Sharon learned from a snitch that he was being tricked, and that his own employees were amassing shares bought on margin—meaning they were borrowing money from a broker and pledging their shares as collateral. This left them vulnerable.

What Sharon did next was cunning and willful. He began selling Crown Point shares in indigestible blocks every thirty minutes. This drove the price of Crown Point down from $1,875 per share to less than $100. The attack on Crown Point was so overwhelming that margin calls were triggered across the exchange. The prices of other shares fell as well. Sharon bought the whole lot—including Crown Point—at distressed prices, netting some $5 million and inflicting a $3 million loss on his challengers.[2]

“Everybody gambled in stocks,” Bryce wrote, “from the railroad kings down to the maidservants.”

What did Newlands make of this? Newlands accepted Sharon and San Francisco as they were in the early 1870s. He lived in a time and a place where things were wide open, and where the people liked it that way. In the American Commonwealth, Bryce singled out how San Franciscans sided with the speculator. “Everybody gambled in stocks,” Bryce wrote, “from the railroad kings down to the maidservants.”[3]

At ease with his hard-charging father-in-law, Newlands moved into the Sharon house, where he and Clara had their own quarters. He simultaneously moved into the big leagues in business. Newlands became counsel to the Bank of California and the Spring Valley Water Works. He was given a choice office in the first-class building immediately across the street from the Bank of California. His office was on the second floor, with French doors opening out to face the doors of the bank. He could not have imagined what he was soon to see—riots, despair, and a suicide.

[1] William M. Stewart, Reminiscences of Senator William M. Stewart of Nevada (Neale Publishing Company, 1908), p. 261.

[2] May 15, 1872 became one of San Francisco’s days famous for speculation in mining stocks. An excellent book on that day, and on the Comstock, is Eliot Lord, Comstock Mining and Miners (US Geological Survey, 1883), reprinted by Howell: Berkeley, 1959, see stock tables on p. 292 for May 15, 1872. See also George Lyman, Ralston’s Ring (Scribner’s: NY, 1937) 210-219; Theodore Hittell, California, IV, 541-44

[3] Bryce, V2, p. 1070.