Chapter 6 - “Mr. Sharon and Lady”

Just as Frank Newlands was riding high, it all came crashing down. No sooner had Newlands successfully managed the regulation of the Spring Valley water company then a succession of freakish events transpired that would socially disgrace him in San Francisco and force him to Nevada. The bizarre events involved the richest man in the city—his father-in-law—and they centered on sex.

Things began in a small way in the small frontier town of Virginia City, Nevada. William Sharon liked sex, and he treated it like a business. By the mid-1860s, Sharon had become the “king of the Comstock,” having vertically integrated most of the mining-related businesses in Virginia City. He had also started a little sex business. Sharon began the decade seeing Belle Warner, a local courtesan, on a regular basis. He helped her set up her own business, managing a string of young women on his behalf. He paid her a monthly retainer and regularly escorted Belle’s employees to the Glenbrook Hotel—co-owned by Sharon and Ralston—where he signed in as “Mr. Sharon and lady.” It was a tidy little business in a small town with 49 saloons and an established prostitution district. That was Virginia City in the 1860s. Nobody cared as long as there was no commotion.[1]

San Francisco in the 1880s was another matter. The San Francisco Sharon had entered in 1850 was still partly a tent city, not so different from Virginia City at its inception. Three decades later, San Francisco prided itself on its sophistication.[2] The city by the bay boasted stately office buildings and grand hotels. It was known for its many restaurants, so many that “restaurant living”—eating out every night—was possible. At 60 years old, Sharon was a U.S. Senator and the richest man in the city. He expected that his business in sex would continue as before.

He was wrong. Sharon’s ego hid from him that he was too old for the pace of a Virginia City lifestyle. Most important, his ego blinded him from seeing that—when it came to sex—the roles were reversed. Rich, old, and easily dazzled, Sharon was now the prey.

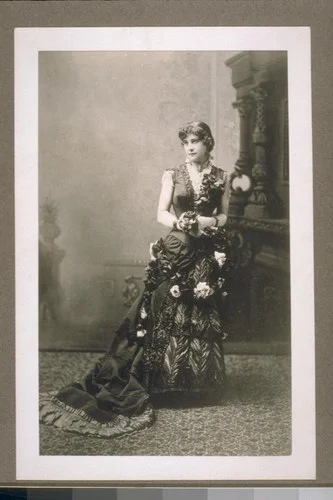

Sarah Althea Hill captured Sharon for one year, in 1880, and he never got rid of her. Attractive, sensuous, and haughty, she cost him almost everything—his health, his prominence, his California residence, and the respect of his family. Sharon kept his estate away from Sarah, but in the process forced his children to live in dusty Nevada.

When Sharon started seeing Sarah, he was a sitting U.S. Senator—in name only. Even by Gilded Age standards, Sharon’s performance in public office was pitiful. Whereas Stewart, his predecessor, was credited with authoring the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution that protected voting rights, Sharon was almost two years late getting sworn in. Finding Washington dull and legislative sessions boring, Sharon attended only three of the Senate’s six sessions. He voted hardly at all and spoke on the Senate floor but once, explaining that he had been too busy to be a Senator.[3] He never once visited his Nevada constituency.

As a Senator, Sharon kept busy chasing two old favorites—land and ladies. When in the capital, Sharon’s biggest occupation was speculating in real estate. He had an eye for buying the right raw land just before it was developed. He had done it in St. Louis in the 1840s and in San Francisco in the 1850s and 1870s. In Washington, Sharon bought land in what was to become Dupont Circle. So shrewd was this investment that, a decade later, Newlands was to sell the Dupont Circle parcels and develop Chevy Chase, the country’s first “suburban new town.”[4]

The relationship with Sarah began in the spring of 1880. It is unclear who picked up whom. They met in the bar at the Grand Hotel, a Sharon property across Montgomery Street from the Palace. After a spell, they adjourned to Sharon’s suite at the Palace. An affair began. Soon, Sharon started making the kinds of mistakes he usually avoided. He installed Sarah in one of the Grand’s special suites, where he lived openly with her, on and off. And he encouraged her to play hostess at parties given at his Belmont beach residence 23 miles south of the city.

Sometime in 1881, Sharon tired of Sarah. He ended the affair and had her evicted from the Grand. Astonishingly, he started seeing no fewer than eight other women. Sarah would have none of it. She claimed that she and Sharon were in love and that Sharon had married her secretly on August 8, 1880. Sharon ignored her.

On September 8, 1883, Sarah had Sharon arrested for adultery. It was the first shot fired in a lengthy imbroglio. Sharon’s lawyers had the charge dismissed, contending that Sharon was not married to Sarah and, moreover, that adultery was not a crime in California. Sarah promptly sued for divorce, claiming to be in possession of a secret marriage contract with Sharon. Sarah filed her suit in the city’s superior court, part of the state court system. Sharon counter-sued in federal circuit court, claiming Nevada citizenship.

So began what became one of the era’s most high-profile and ill-fated court cases, breathlessly covered as far away as New York and London. It dragged on for five years. By the time the dust settled, Sharon had died, Sarah had gone insane, court bailiffs had been beaten up, a former chief justice of the state supreme court was jailed and then shot by a U.S. Marshal, and a United States Supreme Court Justice was attacked.[5]

Upon Sharon’s death, Newlands became the executive trustee for the Sharon estate.

The case ended with decisive rulings from the federal court in 1888, three years after Sharon died of congestive heart failure. Upon Sharon’s death, Newlands became the executive trustee for the Sharon estate. He left nothing to chance. Along with all the heirs to Sharon’s estate, Newlands moved to Nevada, thereby maintaining Sharon’s Nevada citizenship and protection under federal courts.[6] Newlands found Nevada drab and dull. But in it, he also found the makings of his own political future.

[1] Makley, Sharon, pp. 66-102 provides a detailed, matter-of-fact account of Sharon in Virginia City (population 2,345 in 1860). Even toned down, it is one of the great tales of the Wild West. Nevada was a territory until 1864 and Virginia City was a classic frontier town. Mark Twain made Virginia City justifiably notorious for its roughness. His columns in the town’s Territorial Enterprise are reprinted in Mark Twain’s San Francisco which includes Twain’s best from Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise.

[2] Makley, Sharon, p. 157

[3] Makley, Sharon, devotes ch 11, pp. 142-157, to Sharon’s poor Senatorial performance. Nevada newspapers were rough on Sharon. Characteristically, he seemed oblivious to their criticism. Asked by the Territorial Enterprise for his views on Washington, Sharon off-handedly cabled back: “Outside of political circles, it is dull. It never was intended for a city—only as the seat of Government, and excepting when Congress is in session there is very little done.”

[4] Lilley, Early Career, pp. 207-214. Sharon spent $160,000 on Washington real estate. Newlands sold those properties for more than ten times their purchase price about twelve years after Sharon bought them.

[5] The whole affair is covered in detail in Oscar Lewis, Bonanza Inn (Comstock, 1939), pp. 116-214. It contains many reprints of official documents, court testimony, and newspaper articles. The most thorough study of the legal aspects of the case is Oscar T. Shuck, ed., History of the Bench & Bar of California (Los Angeles, CA, 1901 pp. 137-148.)

[6] Newlands to Frederick W. Sharon, February 3, 1888, Sharon Mss, Bancroft Library. Newlands’ wife Clara Sharon had died in 1882 during childbirth. Newlands in 1888 was a single father to three girls—Clara (b. 1875), Janet (b. 1876), and Frances (b. 1878). Sharon died on November 14, 1885 of congestive heart failure. Newlands’ ultimate role as executive trustee was never in question. He was treated as the heir apparent from early on. Sharon’s son (Frederick W. Sharon), who had gone to Harvard but never worked, had resigned from any trustee responsibilities upon his father’s death. The executive authority always was with Newlands. Newlands and Fred were very close, and they had similar interests in cosmopolitan issues like city planning. Newlands dictated a loving reminiscence of his brother-in-law. He made a fuss about Fred winning Harvard’s middleweight boxing championship. The document is in the Sharon mss, Bancroft Library.