Chapter 4 - Ralston’s Ruin

Frank Newlands never complained about the wedding. Nor did his status-conscious mother. At least they never wrote it down. Nor did Newlands ever complain about working for his father-in-law. In fact, he excelled at the job. Newlands knew his way around balance sheets, was adept at managing people, and was a natural at lobbying. His associates found him quiet, loyal, and hardworking. He was, in short, the ideal son-in-law. Before long, thanks to his abundant talents, Newlands had made himself the heir apparent.[1]

Newlands knew his way around balance sheets, was adept at managing people, and was a natural at lobbying.

Just as Newlands’ star was rising, Ralston’s was on the wane. Sharon and Ralston had been a team—and a legal partnership—since 1865. Ralston was Mr. Outside, while Sharon played Mr. Inside. But by 1875, Ralston had gotten himself into trouble. The catastrophic national panic of 1873 had infected the California economy, particularly the silver mining industry. To sustain his many ventures, Ralston had borrowed heavily from “his” bank, otherwise known as the Bank of California. Spring Valley Water Works was the partnership’s “cash-cow” investment. Together, Sharon and Ralston controlled the water monopoly, which paid nine percent interest on its bonds. The bonds did not trade publicly. In Ralston’s Ring, George Lyman claims that Ralston and Sharon owned so much of the bonds—62 percent of 80,000 bonds—that their voting control was never contested.

Ralston cooked up a daring scheme to use Spring Valley as the vehicle to exit his debts. He needed cash—a lot of it—and he needed it fast. So Ralston concocted a plan to expand Spring Valley’s network of reservoirs, thereby rendering the city safe in the worst of drought situations. Ralston would then sell the “improved” package to the city for $15 million. Ralston’s numbers were fuzzy, but the consensus was that Spring Valley—with its new reservoirs added—was a $6 million property, whose sale at $15 million would yield a profit of $9 million. If Spring Valley could fetch that price, with Ralston and Sharon splitting the $9 million profit, Ralston would be able to clear his debts with the bank.[2]

Ralston’s gambit was not a crazy idea. This was San Francisco in 1875. This was the Spring Valley Water Works. Only two cities in the world with populations over 50,000 had privately-held water companies—London and San Francisco. The London company was heavily regulated, San Francisco’s hardly at all. And the history of Spring Valley since its 1858 inception was an encouraging sign for Ralston. When chartered by the legislature, the company’s bonds paid 20 percent, competition was prohibited, and the company had the power of eminent domain. Spring Valley had a reputation for prohibitive rates and lousy distribution.

Only two cities in the world with populations over 50,000 had privately-held water companies—London and San Francisco.

But Ralston miscalculated—fatally. In 1874, in a feeble effort at reform, the California state legislature had reduced the rates to nine percent interest and created a surveying commission to identify alternative reservoir sites. The commission published its survey on March 18, 1875, at which point the press discovered that Ralston had already bought the alternative sites and cornered all the water. An outcry arose, in both San Francisco and Sacramento. By August of 1875, with Spring Valley still unsold and gossip running wild, the Bank of California was struggling to meet the mini runs on it. At 2:35 pm on August 26, 1875, the bank ran out of cash and closed its doors. Rioting broke out in the street. Newlands watched it all, “a vista of horror.”

In the center of the maelstrom was his father-in-law’s erstwhile business partner. A broken man, Ralston could go on no longer. As Newlands looked on, Ralston “took his hat and walked from the bank. The object of his pride and solicitude, the victim of his folly.” He “went to the ocean beach, looked through the Golden Gate... and swam to a point whence it was impossible to return.”[3] Water had built Ralston up and laid him low. Tragically but fittingly, it was to the deep that he commended his soul.

Upon Ralston’s untimely demise, Newlands assumed many of Ralston’s roles in the Sharon partnership. He slipped seamlessly from the role of counsel to that of consigliere, becoming a public face for the Sharon interests. Much of the work that Newlands had thrust upon him involved cleaning up after Ralston’s booster-ish optimism.

The work shaped Newlands’ thinking in a very particular way. He inherited businesses that had been built with a regional emphasis, not a local one. He also inherited businesses that ran on technical expertise. Both Ralston and Sharon were inclined towards these approaches. Their early business coup had been the breaking open of the Comstock mines, an operation which, from the start, spanned 2 states and 200 miles. Technical experts helped Ralston and Sharon mine at 500 feet and bring water to Virginia City through seven miles of Sierra Nevada mountains. Ralston and Sharon had built and managed stamping mills, a railroad, and a water company. And they developed systems to move silver rapidly from the mines of Nevada to the bank in San Francisco.

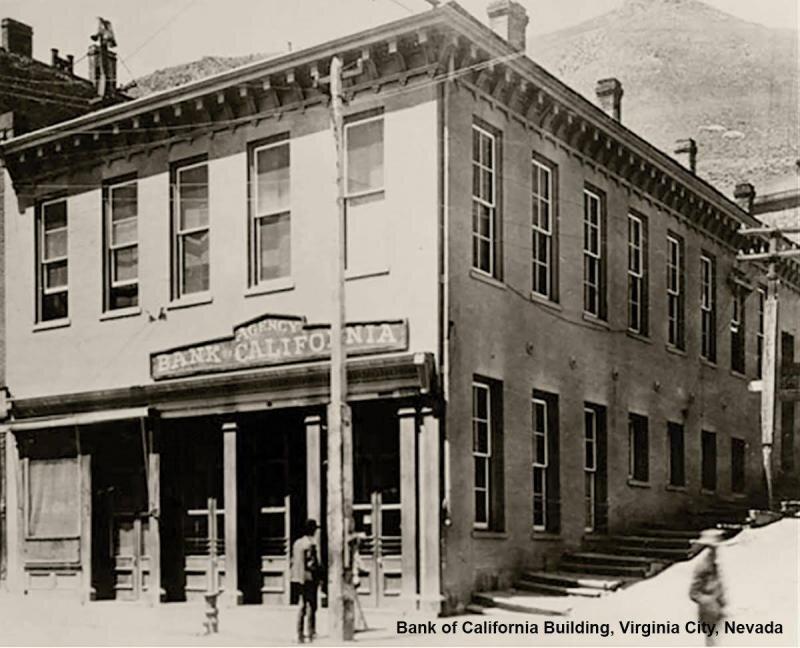

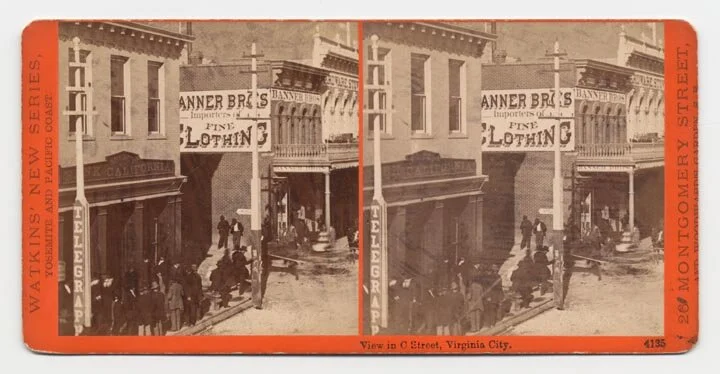

Figure 4.1: The Bank of California

Figure 4.2: The photos of the Bank of California were taken by Carleton Watkins, illustrious photographer of western landscapes and work sites. The photographs capture the low-budget look of the Sharon bank. The stereopticon shot by Watkins, taken in the afternoon, shows the heavy foot traffic at the bank. Sharon’s living quarters, facing out onto C Street, are on the second floor with the windows open. Sharon lived on the town’s edge where the paths went up to the mines.

The other enterprises these two men created similarly reflected their regional and technical emphasis. The Bank of California was run as the big bank for the West Coast. Together, Sharon and Ralston built the West’s first deluxe hotel, the Palace, which they marketed as a “destination hotel” for East Coast and international travelers. Their Spring Valley Water Works drew its supply from reservoirs in distant counties. The water company’s key man was German-born engineer Hermann Schussler, a water-systems engineer and dam architect. Newlands had the luxury of starting at the top of businesses that required him to think regionally and to think like an expert.

Ralston’s death pitched Newlands into the recapitalization of the Bank of California. This was tricky business. The regional economy was in bad shape. The faltering bank was the region’s pre-eminent financial institution. With it teetering on the brink, San Francisco—that turbulent city Bryce had deemed like no other in the United States—was melting down.

Moving quickly to avert catastrophe, Sharon called in favors and raised a rescue package of $7 million. Rescuing the bank then fell to Newlands. The exceedingly delicate task facing him was to carve out of the $7 million enough new capital to open the bank, all while liquidating the $4 million in debts the bank held against the Ralston estate. Even more vexingly, some of the Ralston assets (all hard to value in depressed times) overlapped with the Ralston-Sharon partnership. If Newlands paid out one hundred cents on the dollar for Ralston’s debts, it might liquidate the entire estate and encroach on the Ralston-Sharon partnership—and his father-in-law’s fortune.

Citing the hard times and depressed values of the assets, Newlands cajoled Ralston’s creditors into taking 50 cents on the dollar. Though he later acknowledged that he had dealt too sharply—and, in a prominent subsequent court case, increased the payout to a persistent creditor[4]—Newlands never agonized over his role in the recapitalization. He had a panic on his hands, and a bank to get back on its feet. He got the job done in 37 days. On October 2, 1875, just over a month after the runs and riots that closed its doors, the Bank of California resumed normal operations.

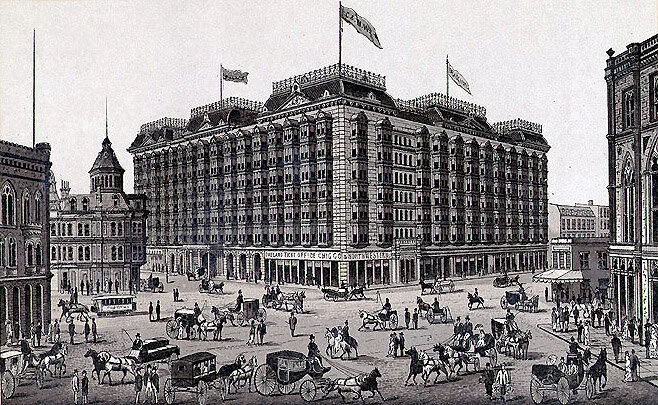

Newlands hardly had a moment to savor his triumph. Mere weeks later, on October 15, he assumed oversight of the Palace Hotel. The hotel opened to great reviews in 1875, but ran in the red from the start. The problem, once again, was Ralston. He had thought too grand. True to its name, the Palace was the largest hotel in the West. It soared 120 feet above San Francisco’s bustling streets, the tallest building in the city. Guests had their pick of 755 luxury rooms, a first-rate dining room, banquet facilities, and shops. And they could delight in each room’s private bathroom and electronic intercom system, as well as the handsomely-appointed hydraulic elevators known as “rising rooms.”

Figure 4.3: San Francisco’s Palace Hotel opened in 1875. From its inception, the hotel figured prominently in the city’s imagination. William Ralston designed the hotel, William Sharon financed it and Francis Newlands managed it. It was built to be big and grand. With 755 rooms, hydraulic elevators (“rising rooms”) a first-class restaurant, and luxury shops, the hotel attracted travelers from the East Coast and London. Oscar Lewis wrote a fine book Bonanza Inn (1939) about the Palace and its mark on San Francisco. It is still in print.

To oversee the hotel operations more closely, Newlands and his family moved into the hotel. Two adjacent suites were connected for Frank and Clara and their two daughters, Clara and Janet. For five years, home was the towering edifice at the corner of Market and Montgomery Street. The girls loved every second of it, but for their father, being “overseer” was a trial. The hotel was geared to serve business and tourist travel, yet the aftershocks of the panic of 1873 meant the economy was faltering. Costs could be “managed down” only so far. Yet there was a silver lining. Living at the Palace—and shouldering the responsibility of running it—further exposed Newlands to life in the regional business world.[5]

Having put the Bank of California and the Palace on firmer footing, Newlands turned his attention to resolving the Spring Valley furor that Ralston had ignited. Ralston’s water monopoly was still intact and just as controversial, with Sharon replacing Ralston as the major owner. In December of 1875, the state legislature met in Sacramento, determined to deal with the matter. Sharon put Newlands in charge of the work in Sacramento—and Newlands, once more, stepped into the breach.

It would be an uphill battle. As Newlands wrote to Sharon in a letter the following March, the legislature was awash in bills hostile to their interests.[6] Newlands hired an army of lobbyists, who identified three assembly bills as especially threatening. Taken together, this legislation gave the board of supervisors tough rate-making powers over the water company, which threatened to undo the sacrosanct 9 percent interest and Spring Valley’s cash cow status. The Assembly was chaotic, but with the exertions of Newlands and his lobbyists the bills were defeated.

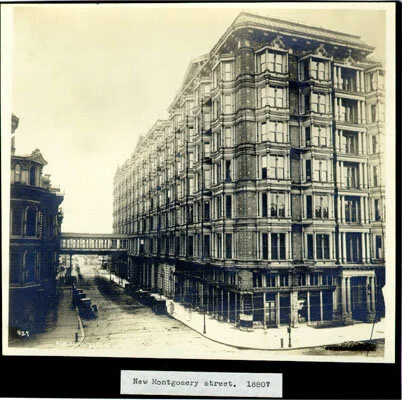

Figure 4.4 : The photo captures the grandness of the courtyard entrance to the hotel. The scale is big and the taste is opulent.

Figure 4.5 : Palace Hotel & Grand Hotel. San Francisco 1880s. Sharon owned both. The second-floor, covered passageway is rich in local lore. Allegedly, businessmen had meetings in the more lavish Palace Hotel and stashed women in the simpler Grand. The covered passageway kept the comings and goings off the streets.

But a fourth bill loomed, which Newlands deemed the most troubling. This bill, championed by an Assemblyman named Rogers, would have authorized an alternative—and publicly-owned—competitor to Spring Valley. To Newlands’ great chagrin, the bill passed the Assembly. Newlands worked to get “six or seven amendments” added to the Senate bill. He boasted that the amendments were “not very skillfully drawn,” with the effect of gutting the bill. Newlands was pleased with himself; Spring Valley had once again weathered the storm of legislative reform. In fact, as Newlands crowed when he sent Sharon a copy of the amended bill, he had let the so-called Rogers Act pass deliberately.

Why the seeming about-face? The answer is that Newlands intended to bring back the old Ralston scheme. The Rogers Act authorized a publicly-held water company—overseen by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors—and Newlands intended to sell them his father-in-law’s water company at a tidy profit. As he advised Sharon, by selling Spring Valley to the city—thereby making it publicly owned—they stood to reap 12 or 13 million dollars. Shrewdly, Newlands realized that it would behoove Spring Valley to appear supportive of a public water entity, if only to improve their chances of a sale.

Newlands wrote Sharon that “given the condition of public sentiment,” the Supervisors would pay no more than $13 million, provided the package included Ralston’s additional reservoirs and water catchment sites. Sell them all, Newlands told Sharon, but hold back on the Calaveras site, which “is generally considered a humbug.”

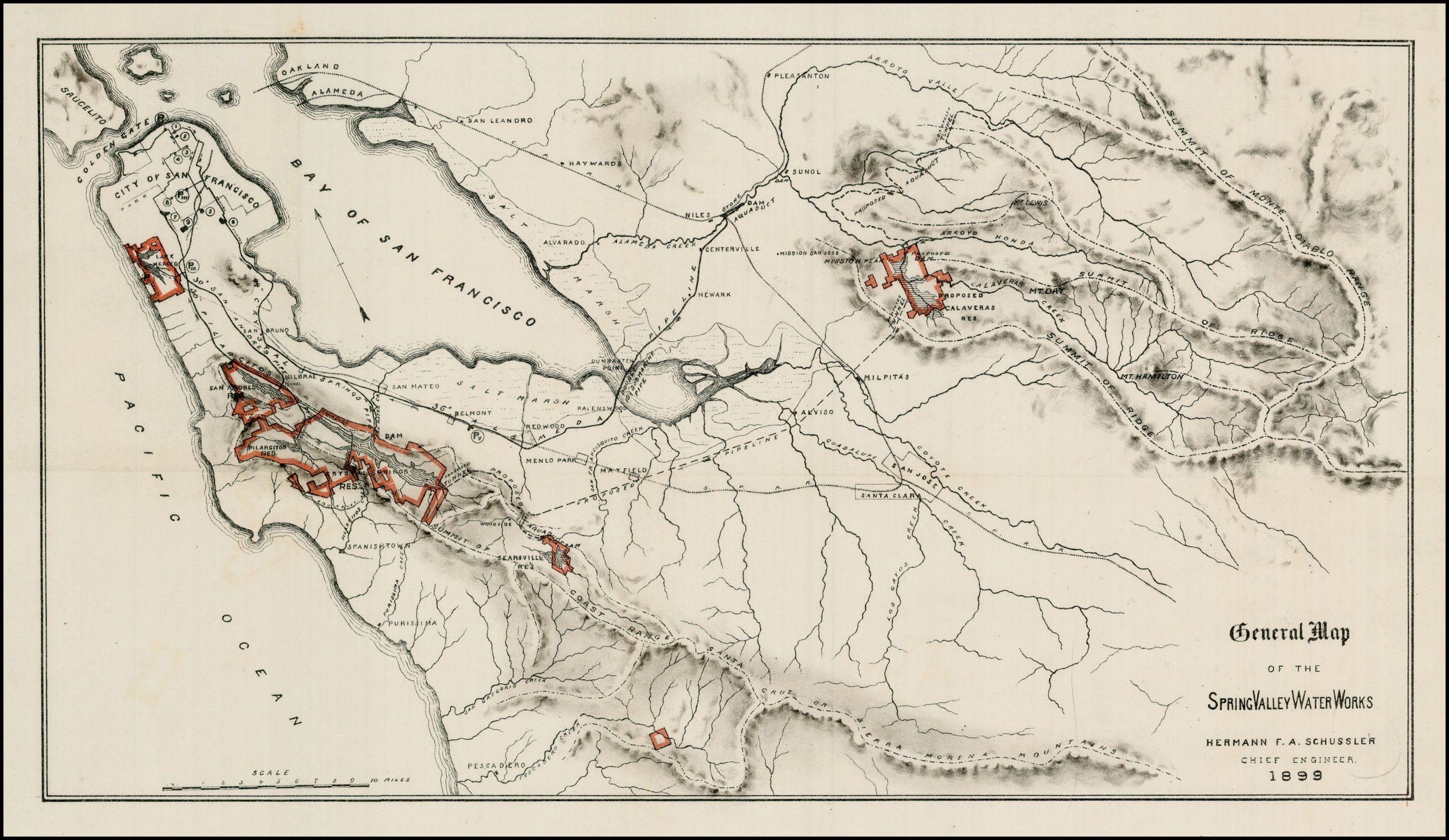

In truth, Newlands thought it far from “a humbug.” He and Hermann Schussler, the company’s water engineering expert, both thought highly of the Calaveras site.[7] Schussler drew a map (shown below), which illustrated vividly the complicated regional enterprise that was Spring Valley. Yet the ingenious engineer was confident that he could run pipe for the 53 miles northwest from Calaveras into San Francisco, For his part, Newlands believed that once Spring Valley was purchased, the supervisors would “be forced” in two years to buy Calaveras, “and here the great profit can be made.”[8]

For a relative novice in state politics, Newlands had emerged from Sacramento with an impressive bounty. His legislative maneuvering would enable Sharon to “double dip” off the supposedly reformist Rogers Act.[9] Out of the ruins of Ralston’s overreach, Frank Newlands had further solidified his family’s fortune.

Figure 4.6: A map illustrating how Spring Valley’s water sources encircle San Francisco. This map was prepared by the company’s chief engineer, Hermann F.A. Schussler, a brilliant engineer and skilled businessman who was a prominent force in the water company. Schussler’s map shows that Spring Valley’s operations were necessarily regional in character, drawing water from reservoirs in Santa Clara, Alameda and San Mateo counties. Courtesy of Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection, Stanford University

[1] Hubert H. Bancroft, Chronicles of the Builders of the Commonwealth (San Francisco, 1892) IV, 29

[2] Lyman’s Ralston’s Ring, pp. 262-323, is the most detailed account of Ralston’s spectacular fall. Both the water company and the bank are covered. The book reprints many documents and is footnoted extensively.

[3] San Francisco Bulletin, October 10, 1884, from Newlands' testimony in Odd Fellows Bank v. William Sharon. The bank panic and Ralston suicide drew national attention. A good summary (and dramatic art) is in Harper’ s Weekly, v.19, September 27, 1875, p. 776.

[4] Newlands testimony, Odd Fellows Bank v William Sharon, San Francisco Bulletin, October 13, 1884; Lilley, “Early Career,” pp. 62-65.

[5] Conversation with Janet Newlands Johnston, September 1963, in Truckee, NV. Palace Hotel, San Francisco, in Wikipedia, retrieved May 7, 2019 gives all the details on the “outsized” dimensions of the hotel. Oscar Lewis, Bonanza Inn (Comstock, 1939) is good on the hotel’s place in the imagination of San Francisco. Lewis makes much of how Ralston designed and built it, but Sharon opened and ran it.

[6] The lobbying incident is taken from a long letter that Newlands sent to Sharon, March 30, 1876, Newlands Mss.

[7] Schussler and Newlands were right about Calaveras. Schussler stayed in his office at Spring Valley long enough to make the Calaveras acquisition in 1902. See San Francisco Call, October 22, 1902: Spring Valley’s Water Monopoly Now Controls Entire Santa Clara County Watershed. For the history of the Calaveras scheme, see Theodore Hittell, California, IV, 554.

[8] Newlands letter to Sharon, March 30, 1876.

[9] Makley, Sharon, pp. 40, 145-146.